One feature common to all living systems is the requirement to generate mechanical forces that are fueled by chemical energy. For example, cells need to generate force to separate double stranded DNA to enable replication. Bacteria use ATP to power their flagella to move, and animals use ATP to drive muscle contraction and locomotion. Motor proteins, such as kinesin, dynein, and myosin, function by hydrolyzing ATP to change conformation and mediate movement. One grand challenge in the field is to develop synthetic versions of molecular motors and nanoscale machines. The motivation for making synthetic versions of motor proteins comes from anticipation that such devices could be used to power the next era of the industrial revolution – allowing society to make new classes of sensors, robots, computers and drugs with powerful capabilities. Indeed, this notion that we can create nanoscale devices and machines has inspired generations of fiction and non-fiction such as Eric Drexler’s Engines of Creation and Michael Crichton’s Prey.

Unfortunately, synthetic machines are still in their infancy. For example, we still don’t know how to miniaturize machines down to the molecular scale and still efficiently convert chemical energy to generate processive mechanical work. The motivation driving research under the DNA devices and motors subgroup is to address this grand challenge and to develop the basic blueprints for how to build synthetic machines that start to replicate the features of biological motors.

The following describes a brief chronological account of our contributions followed by a future outlook.

RNase H-powered Rolling motors

Our first “step” into this field was more of a “roll” with the development of the RNase H-powered high speed rolling motors that was reported in 2016. Most synthetic motor constructs worked by utilizing a bipedal – two legged - walker to move a motor along a DNA or RNA track. Leg binding induced hydrolysis of a “foothold” site on the track and this allowed for locomotion. The problem with this design was that motors frequently dissociated from the track because if both legs lost their footholds, then motors were lost to the bulk. Conversely, motors with many legs solved the dissociation problem but showed negligible speed because the leg movements were not coordinated. We solved the problem by 1) increasing leg polyvalency by orders of magnitude, 2) employing an enzyme with kcat orders of magnitude faster than the commonly used deoxyribozymes, and 3) patterning legs on a rigid spherical chassis that facilitates leg-to-leg coordination.

(Left) Motor chassis movement tracking in brightfield. (Right) Motor-localized fluorescently-tagged substrate depletion in TRITC.

Motors were comprised of micron scale silica spheres densely coated with DNA legs and allowed to bind a surface with a dense array of RNA foothold sites. When RNase H was added, motors moved at speeds of up to microns per minute and continued moving for millimeter distances. The video shows our rolling motors where the RNA footholds were tagged with a fluorescence dye. This first report showed that rolling motors exceeded the speed and processivity of all previously reported DNA walkers. Furthermore, we can monitor these motors in real time on a high-powered microscope, or even with a smartphone camera (Nature Nanotech. 2016)

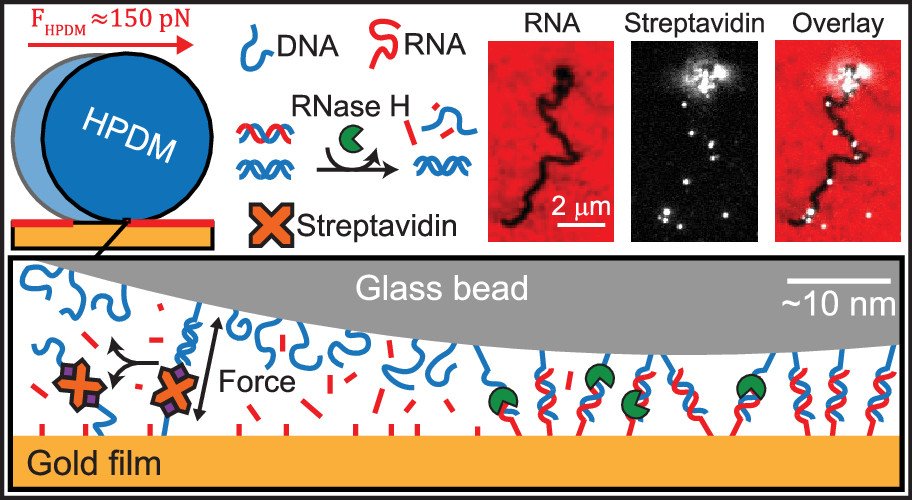

Polyvalent DNA motors can generate 100+ pN of Force

We next asked “How much force is generated by rolling motors?”. To address this question, we created DNA-DNA tethers that acted as a molecular resistive tether that counteracted the force generated by the motors. We used DNA tethers because the forces needed to denature DNA duplexes was already well studied by the biophysics community. We titrated the density of DNA tethers so that we can investigate how many DNA duplexes are needed to overcome the force generated by motors and induce stalling (see figure below). Our work demonstrated that the motors rupture DNA duplexes in both the unzipping and shearing geometries (~12 and ~50pN), and even biotin-streptavidin bonds (~100-150 pN) which are often described as Nature’s strongest non-covalent bonds. Additionally, by utilizing Alexa647 (A647) fluorophore-functionalized streptavidin (SA) molecules this system became capable of molecular lithography. As when the biotin-streptavidin bonds rupture, the A647-SA is left on the substrate surface with the motor’s fluorescently-labelled substrate depletion track, thus depositing bright instances of “molecular ink” onto the a surface. (Nano letters 2019)

Nanoscale motors

We next wanted to investigate the basic rules and blueprints of how motor molecluar design influences its efficiency and activity. To achieve this goal, we created motors comprised of DNA origami which allows for highly precise (angstrom scale) molecular engineering of the chassis and DNA legs of motor. Motors were designed to resemble and “rolling pin” approximately 120 nm long and 20 nm wide. We found that these rod-shaped motors moved by rolling and hence translocated in a linear fashion (ballistically) on the RNA track. Importantly, the work demonstrated that the local DNA leg density and the rigidity of the chassis were critical in boosting motor efficiency. These parameters influence leg-to-leg coordination and rapid fuel consumption. (Angewandte Chemie 2020)

In a separate project, we created gold nanoparticle motors, and demonstrated that this design leads to enhanced speed/processivity. The gold particle “motor chassis” affords key advantages, which include ease of functionalization and display of a high density of DNA legs. In addition, gold particles strongly scatter visible light, providing unprecedented temporal (~50-500 msec) and spatial resolutions (~10 nm) for visualizing nanoscale dynamics. We used modeling and experiments to reveal that increasing leg DNA density boosts motor speed and processivity while DNA leg span only increases processivity. We show that motors translocate by rolling through a number of experiments including the observation that dimerized particles travel more ballistically. Interestingly, we discovered that motors exhibit bursts of high velocity punctuated with transient stalling – which is described as a Levy-type motion and is highly unusual for nanomaterials and typically observed in biological systems like migrating bacteria, birds, and marine predators. (ACS Nano 2022)

DNA computation systems with DNA motors

A major goal in the field is to create nanoscale robots that can deliver drugs, move cargo, and aid in manufacturing. Much of the progress toward DNA robotics has been enabled by nucleic acid reactions that demonstrate Boolean and fuzzy logic operations, which are the pillars of computation. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no examples of DNA computing motors; i.e. DNA machines that consume chemical energy to produce mechanical work and that can sense and process information to guide mechanical activity. Creating genuine nanoscale robotic systems requires the integration of three components: a) chemical (input) sensing, b) information processing, and c) active mechanical function (output). Achieving this goal will also take us a step toward recapitulating basic features of single celled organisms that detect and process chemical information to guide directed motion. This has been a long-desired goal of the field, but there are major hurdles. For example, DNA computing systems are slow, and readout requires bulk fluorescence or single molecule AFM. It is not clear how one can link the input and output functions within a single machine. Indeed in a 2021 review on this topic, Chen and colleagues state that “A simpler and low-cost logic detection platform needs to be developed”.

We address this challenge by generating DNA motors that detect and process chemical inputs and transduce this information into easily detected macroscopic locomotion responses. Specifically, we create programmable DNA-based motors with onboard logic (DMOLs) that perform Boolean functions (NOT, YES, AND, and OR) with 15 min readout times. The logic gates were integrated into our rolling motors. The nucleic acid inputs triggered a binary DMOL response through toehold mediated strand displacement reactions, where 0 = no motion and 1= motion. Importantly, motor output transduces molecular information into macroscopic scale responses that can be detected using a conventional smart phone camera. Additionally, because DMOLs produce motion rather than color or fluorescence as the output, multiple unique DMOLs with different logic operations can be mixed on the same chip to process information in a massively parallelized fashion– and to scales that can never be achieved through fluorescence encoding. As a proof-of-concept of label-free encoding and multiplexing, we mixed three different DMOLs (OR, two-input AND, and three-input AND gates) detecting four nucleic acid inputs and showed that these can be read out in parallel using a smart phone microscope. (Nature Nanotech. 2022)

Time-lapse videos of Cy3 (red), Cy5 (blue) and FAM (green) fluorescence channels overlaid, acquired at 5 s intervals for a duration of 15 min

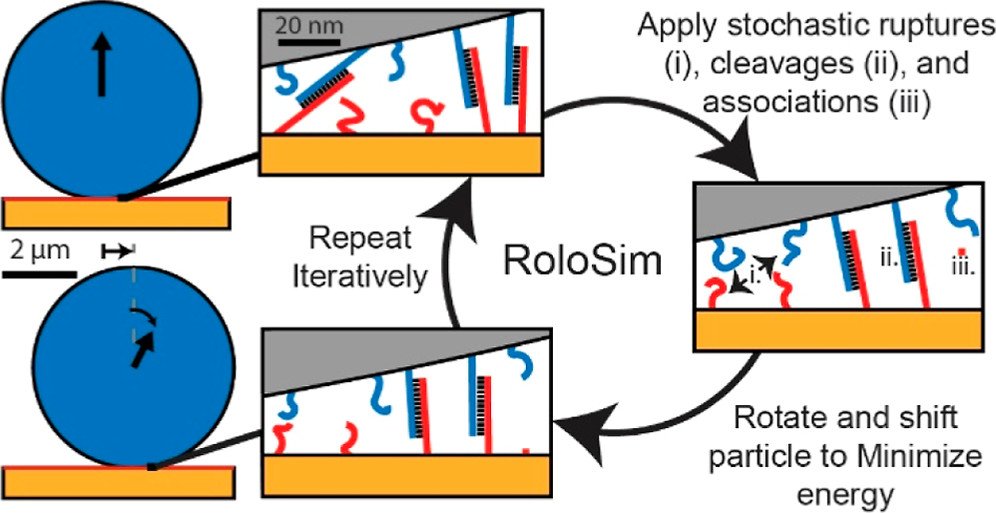

“RoloSim” modeling to predict motor performance

Next, we aimed to create computational models that can predict motor performance. Creating such models is important, as the number of potential parameters that one can tune are enormous and hence very difficulty to test out experimentally. To achieve this goal, we developed RoloSim, an adhesive dynamics software package for fine-grained simulations of motor translocation. RoloSim uses biophysical models for DNA duplex formation and dissociation kinetics to explicitly model tens of thousands of molecular scale interactions. These molecular interactions are then used to calculate the nano- and microscale motions of the motor. We used RoloSim to uncover how motor force and speed scale with several tunable motor properties such as motor size and DNA duplex length. Our results support our previously defined hypothesis that force scales linearly with polyvalency. We also demonstrate that motors can be steered with external force, and we provide design parameters for novel motor-based molecular sensor and nanomachine designs. (J. Phys. Chem. B 2022) Finally, RoloSim predicts the optimal parameters for creating better sensors and these predicts were subsequently validated in our “turbo-charged” motor work (see below).

“Turbo-charged” DNA motors

We next investigated how DNA leg sequence influences the speed and efficiency of motor translocation. DNA rolling motor speeds are largely determined by the interaction of RNase H with the DNA/RNA in the system, but simply increasing [enzyme] results in accelerated hydrolysis of fuel and reduced processivity. Instead, we investigated how DNA sequences influences the rate of DNA leg binding and dissociation from the fuel sites and ultimately tuning motion. By testing different DNA sequences in the substrate, we were able to identify sequences that create “turbo-charged” motors capable of a three-fold increase to instantaneous speed – reaching peak instantaneous velocities of 150 nm/sec. These turbo-charged motors were predicted to generate weaker forces, which should in principle enhance sensitivity when detect target molecules. Indeed, we observed that these motors could detect low copy numbers of DNA – and potentially demonstrate single molecule sensing by monitoring motor net displacements. (Angewandte Chemie 2024)

Timelapse video of the trajectories created by 0%, 33%, and 100% GC motors. The trajectories are centered at (0,0) and color-coded to indicate time. The trajectories were created using the x and y positions of the motors from brightfield particle tracking

Timelapse videos of Cy3 (red) fluorescence channels overlaid with brightfield acquired at 5 s intervals for a duration of 5 mins. The video was acquired ~30 mins after RNase H addition using a 100x 1.49 NA objective. On the left is the 33% GC motor and on the right is the 0% GC motor. The depletion tracks created by each motor are shown in black. Scale bar is 5 μm

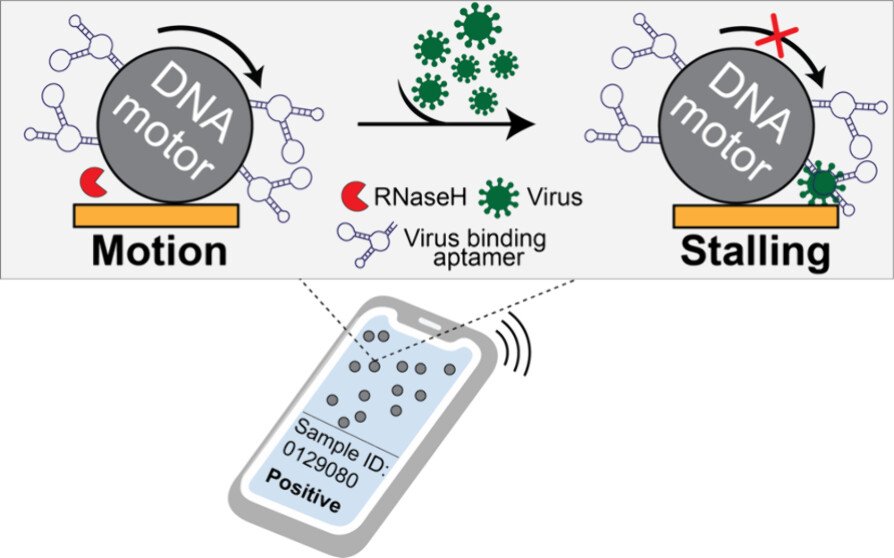

Mechanical virus detection using DNA motors

Our original rolling motor paper suggested that rolling motors could function as sensors of an analyte that mechanically resists motion. In other words, any molecule that stalls the motor could be detected. This is an exciting concept as it represents a fundamentally different approach to analytical chemistry that deviates from the conventional “bind, wash, and transduce” paradigm. Because we started this work during COVID, we decided to focus on detection of viral particles. We termed this strategy as RoloSense, which involves using motor movement to detect the presence of viruses. Here we display virus-specific DNA aptamers on both the motor and the surface. Viruses physically bridge the motor and the surface which induces stalling. Motors perform a “mechanical test” of the viral target and stall in the presence of whole virions, which represents a unique mechanism of transduction distinct from conventional assays. Rolosense can detect SARS-CoV-2 spiked in artificial saliva and exhaled breath condensate with a sensitivity of 10^3 copies/mL and discriminates among other respiratory viruses. The assay is modular and amenable to multiplexing. As a proof of concept, we show that readout can be achieved using a smartphone camera with a microscopic attachment in as little as 15 min without amplification reactions. These results show that mechanical detection using Rolosense can be broadly applied to any viral target and has the potential to enable rapid, low-cost point-of-care screening of circulating viruses. (ACS. Cent. Sci 2024)