Our Lab invented molecular tension fluorescence microscopy

The first approach to map cell traction forces with pN sensitivity!

The cellular response to physical stimuli has been a topic of significant interest in cell biology that range from fundamental developmental biology to cancer diagnostics. For instance, stem cells have been shown to sense and respond to the stiffness of their underlying substrate, steering differentiation based on the mechanical properties of the cellular microenvironment.

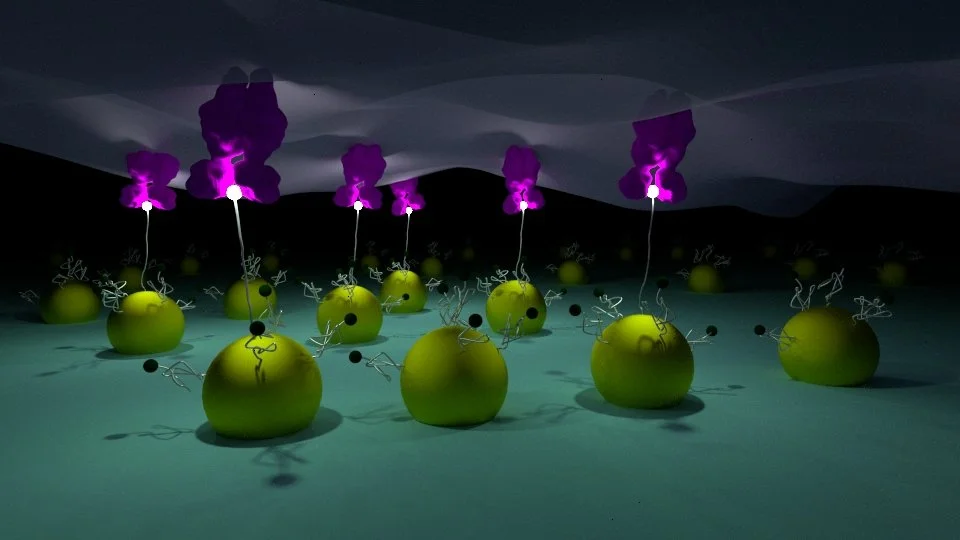

External physical information is transmitted into the cells as the force or tension by cell membrane receptors. Our lab has focused on studying cellular tension at the molecular scale of receptor-ligand interaction and has pioneered this field by developing the first molecular tension probe (Nature Methods, 2011). This initial breakthrough has revolutionized mechanobiology study by providing tools to visualize molecular forces with the speed, convenience, and precision of conventional fluorescence microscopy.

The design of the tension probes is fairly simple and is akin to a macroscopic force gauge. Probes consist of a deformable linker (DNA, protein, or polymer) flanked by a fluorophore and a quencher. These probes are immobilized onto a substrate (glass, lipid bilayer, or hydrogels) and present a biological ligand that engages the receptor of interest. When a cell applies a specific pN forces to stretch the probe, the fluorophore is separated from the quencher, thus leading to an enhancement in signal (up to 100 fold enhancement).

INTEGRIN-MEDIATED MECHANOTRANSDUCTION

Integrins are adhesion receptors that span the plasma membrane and anchor cells to the external environment. We are interested in studying the interplay between mechanical forces and chemical signaling within integrins-mediated adhesions. Our initial work using MTFM showed that integrins can transmit forces>10 pN (JACS 2013). Subsequent work using MTFM probes tethered to patterned nanoparticles showed a relationship between ligand nanoscale spacing and force transmission (Nano Lett. 2014). Building on MTFM technology, we have since investigated processes such as cardiomyocyte differentiation, platelet activation, and inflammatory responses in asthma.

molecular force microscopy (MFM)

Compared with conventional traction force analysis methods, one drawback of molecular tension probe is lacking the information of force direction. To this end, we leveraged molecular tension probes and fluorescence polarization microscopy or structured illumination microscopy to measure the magnitude and 3D orientation of integrin forces. (Nat Methods, 2018 & Nat. Comm., 2021)

Super-resolution Imaging of Integrin-Mediated Cellular force

One of the advantages of molecular tension probes are their nature of detecting force at a single cell receptor-probe interaction. To achieve the higher resolution of cellular force measurement, we first integrated molecular tension probes with the DNA points accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (DNA-PAINT) technique. This tension-PAINT technique has achieved to map piconewton mechanical events with ~25-nm resolution. (Nat. Methods, 2020)

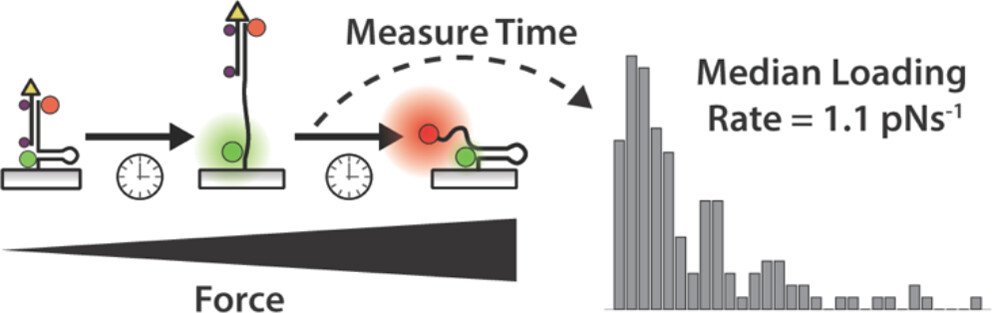

Single molecule tension imaging to study single-receptor force dynamics

One outstanding question in mechanobiology pertains to the dynamics of forces transmitted by mechanoreceptors. How fast does a receptor ramp up mechanical load? How heterogeneous are force ramp rates? These are fundamental questions that remain unresolved and hamper our understanding of mechanotransduction. We addressed this question by integrating the single molecule imaging technique with the molecular tension probe containing two distinct force detection units. Sequential detection of two distinct mechanical events in single molecule resolution allowed one to calculate the force loading rate of integrin-ligand interaction under living cells’ focal adhesion. (JACS 2024)

Mechanically Induced Catalytic Amplification Reaction for Readout of Cellular Forces

Mechanics play a fundamental role in cell biology, but detecting piconewton (pN) forces is challenging because of a lack of accessible and high throughput assays. In this project, we are developing mechanically induced catalytic amplification reactions (MCR) for readout of cell forces. As a proof of concept, the assay was used to test the activity of a mechanomodulatory drugs and integrin adhesion receptor antibodies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a catalytic reaction triggered in response to molecular piconewton forces. The MCR may transform the field of mechanobiology by providing a new facile tool to detect receptor specific mechanics with the convenience of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (Nat. Biomed. Eng., 2023)

Force-induced Cell Tagging technique

Flow cytometry is used routinely to measure single-cell gene expression by staining cells with fluorescent antibodies and nucleic acids. In this project, we developed a new approach to tag mechanically active cells. We named the technique tension-activated cell tagging (TaCT) which labels cells fluorescently based on the magnitude of molecular force transmitted through cell adhesion receptors. As a proof-of-concept, we analyzed fibroblasts and mouse platelets after TaCT using conventional flow cytometry. (Nat. Methods, 2023)

Force-Selective Drug Delivery

The mechanical dysregulation of cells is associated with a number of disease states, that spans from fibrosis to tumorigenesis. Hence, it is highly desirable to develop strategies to deliver drugs based on the “mechanical phenotype” of a cell. To achieve this goal, we developed DNA mechanocapsules (DMCs) comprised of DNA tetrahedrons that are force responsive. DMCs are designed to encapsulate macromolecular cargos such as dextran and oligonucleotide drugs with minimal cargo leakage. We demonstrated force-induced mRNA knockdown of HIF-1α in a manner that is dependent on the magnitude of cellular traction forces. (Nat. Comms. 2024)

Future directions

Despite our contributions to over a decade of tool development in the area of molecular mechanobiology, we still see many questions that need to be answered. What is the relationship between molecular force and receptor conformation? Does the magnitude, orientation, and dynamics of force impact biochemical signaling? Are the measured forces on a substrate similar to those in vivo? How do different types of posttranslational modifications alter mechanobiology? What is the role of the plasma membrane in force transmission? As you see, we are still in the infancy of this field and the development of new tools is badly needed.